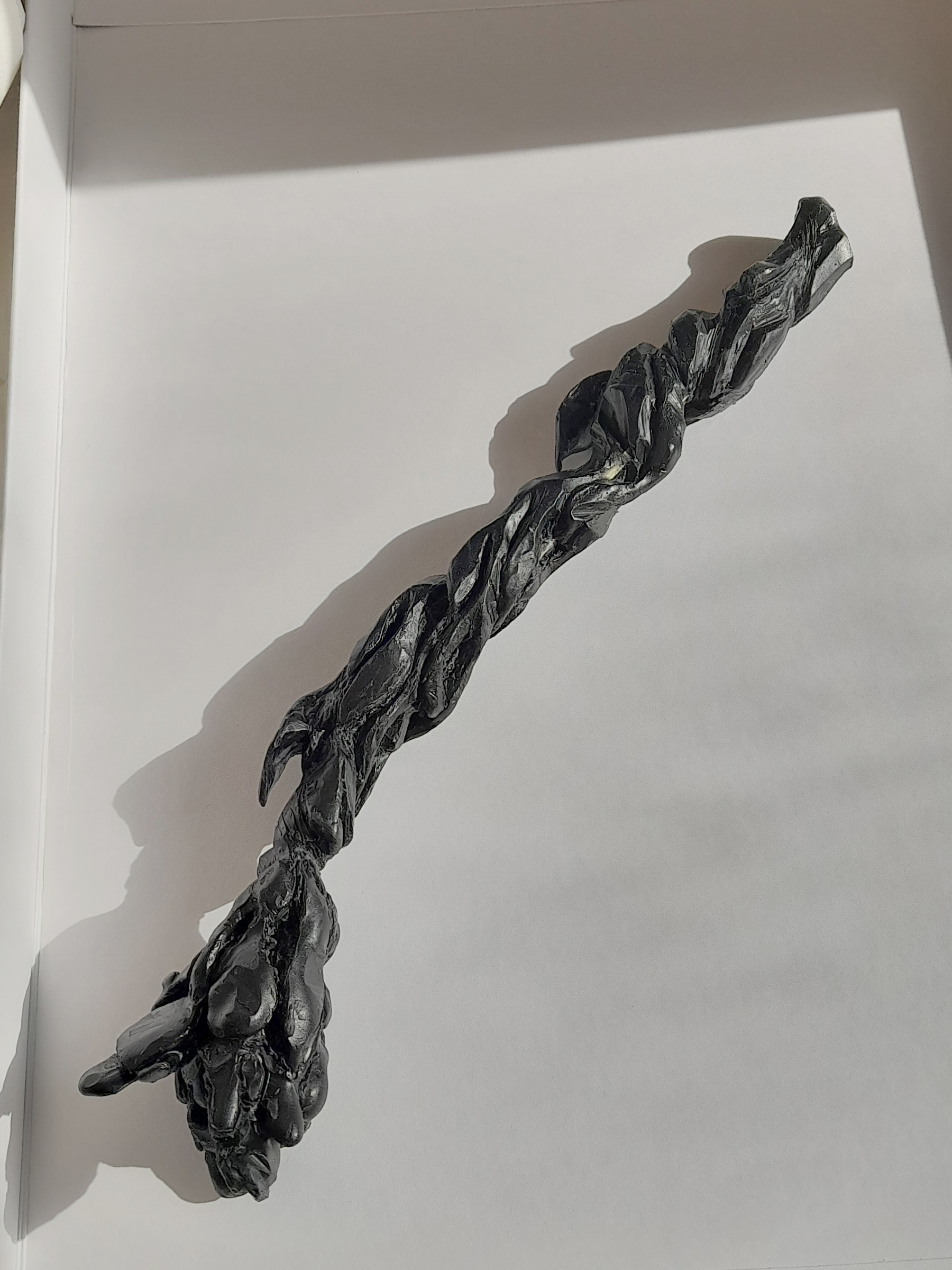

This year, The Hague visual artist Kim David Bots created, for winners as well as nominees, a unique ‘ritual object’, accompanied by a text describing its supposed use or its fictitious history, or providing an instruction. According to Kim, the mere fact that one possesses an object that might be used to perform a ritual, makes a difference.

Necessity

Kim sees rituals as a kind of habits, where the repetition of certain actions is meaningful in itself. In that sense, one might also see artistic practice as a ritual. “Questions about meaning are very intimidating, especially for young artists,” says Kim. “At that stage you still have the idea that you must be able to provide clear answers, but actually such questions are not really relevant. After all, there are countless possible meanings. I think many makers don’t have clear-cut thoughts about the meaning of their work.” Asking yourself whether there is a need for your art seems to him counterproductive. “I think recognizing your own necessity is more important. Why do you feel a certain necessity to do things and how do you give a concrete form to this necessity? If you invest enough time in your practice, you will have no trouble finding out what is necessary for you and how to deal with that.”

He thinks Frederik Hendrik Piket was aware of this: “Artists need time to find out what their necessities are. By buying their work, Piket gave people the opportunity to do so. I think that’s a very beautiful position for a collector. I have this idea that Piket did not care very much about the prestige of the objects he collected, but just wanted to support the practice of certain makers.”

Niels Bohr’s horseshoe

The idea for the award started with an anecdote about the famous Danish physicist Niels Bohr. Bohr often went to a little cottage in the country, which had a horseshoe above the door. A friend who visited him there thought it all rather ridiculous: “Come on, you’re a scientist! You don’t believe in this nonsense, do you?” And the Nobel Prize winner said: “No, I don’t, but I’ve heard that it works, even if you don’t believe in it.”

For Kim, ritual artefacts are objects which attempt to tell a story – objects with agency. Bohr’s reaction shows that you can simply be receptive to that agency. Who knows what such an object may set in motion. “Therefore, the mere fact that you possess an object that might be used to perform a ritual, makes a difference,” Kim says. He sees each of the objects he created for the Piket Art Prizes as a dialogue between himself and the other makers: “A gift in the form of a potential ritual, that could be carried out at the start of a new project, choreography or performance.”

Aluminium

The objects are made of aluminium. “They are all different and each object has its own ‘logic’,” Kim explains. “I first made wax versions which I used as a basis for a mold. I collaborated with Sjuul Joosen, an artist friend who built his own aluminium smelter. I had never worked with aluminium before. It was something I had wanted to do for a very long time, and then the invitation from Piket Art Prizes arrived!” Each of the objects has a box that may also serve as a pedestal. “The objects have a kind of archeological feel, and I have this fantasy that, in fifty years’ time, one of them turns up in a second-hand shop, making someone wonder, ‘Now what have we got here?!’”

Sea mist

Kim David Bots was born in Amsterdam, where he exhibited at Arti et Amicitiae, in the Amsterdam Royal Palace, and at Unfair Amsterdam. After a residency with Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels, he actually wanted to move back to Amsterdam. “But my rent had doubled and so I ended up with artist initiative Billytown, here in The Hague. It was meant as a temporary solution, but I never left. For me, The Hague is the most pleasant of Dutch towns, but I suppose this also has to do with my personality. The Hague is a bit of a village, it has a certain cosiness. And it has this elongated form, like a worm along the coast. There are few cities in the Netherlands where geographical location has such an effect. There’s always wind and in May you often have this sudden cold mist from the sea drifting into the city streets like a ghost.” In 2017 Kim received a PRO Invest subvention from The Hague art centre STROOM to support the development of his work and artistic practice. In 2018 STROOM presented his exhibition Mop Systems. This summer Kim participated in the exhibition Shoeglazing at The Hague gallery Dürst Britt & Mayhew. Another participant was Afra Eisma, who was nominated for the Piket Art Prizes in the Painting category in 2020. Dürst Britt & Mayhew also showed work by Lennart Lahuis, one of the 2015 Piket Art Prizes winners.

Illustration

In Kim’s large Billytown studio there is a lot that refers to his background in illustration. “Every art field has its own kind of academic branch studying it and reflecting on it,” Kim says, “but there’s little reflection on illustration, which means that it’s often underestimated. Illustration is an outstanding means to link imagery and ideology. One example is the Corporate Memphis style, used by tech companies and governments to suggest an eco-friendly, progressive attitude, whereas in fact they’re acting in quite the opposite manner. In addition, illustrations are able to ‘infect’ a text. The first thing you see, even before you start reading, is the image. And you subsequently read the text, often without being aware of it, through the lens of the image. Illustration uses a plethora of references, which are so recognizable that you hardly think about it. Think of the iconic little ‘monopoly man’: a top hat, a white moustache, a monocle. This little figure has become synonymous with greed, power, and real estate as a problematic economic tool. It carries one hundred years of references and stories – you may not know them, but you do get the message. The strength of illustration is that it’s able to create this kind of imagery and make it part of a collective frame of reference within a relatively short time. And all of this happens in a rather non-descript, ‘invisible’ way.” As a result of his fascination with the interaction of word and image, Kim now does a lot with text and audio, too. In November 2022 Kim will start a residency at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht, a post-academic institute for art, design, and reflection, which offers artists time, space, and expertise to deepen their artistic practice. But he’ll be back in The Hague, that’s for sure.

Text: Anna Beerens